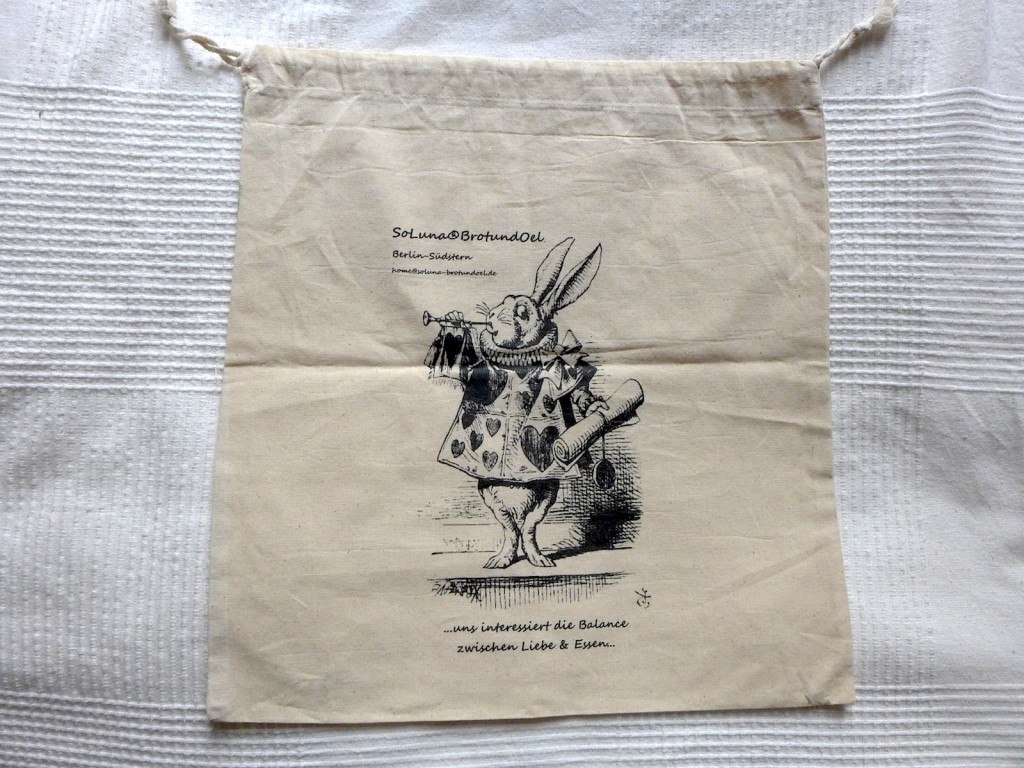

It says a great deal about Peter Klann – until his death just over a year ago the guiding spirit of the Soluna Bakery in Berlin – that he should have chosen a white rabbit as the symbol for his central idea: “…we are interested in the balance between love and food.” “We” meant Peter and his team at Soluna, and by “food” he meant first and foremost bread. For him love was many things, beginning with his wife Miriam, his family and many friends, but also extending far beyond this circle until it became something all-encompassing that defied expression in words, including, of course, these words.

It says a great deal about Peter Klann – until his death just over a year ago the guiding spirit of the Soluna Bakery in Berlin – that he should have chosen a white rabbit as the symbol for his central idea: “…we are interested in the balance between love and food.” “We” meant Peter and his team at Soluna, and by “food” he meant first and foremost bread. For him love was many things, beginning with his wife Miriam, his family and many friends, but also extending far beyond this circle until it became something all-encompassing that defied expression in words, including, of course, these words.

Because Peter had worked as roadie for 20 years during which period he experimented with many consciousness-altering substances the symbol for all this had to be a white rabbit. Think of Jefferson Starship’s psychedelic song ‘White Rabbit’ while looking at this Alfred Tenniel illustration from Lewis Carrol’s Alice in Wonderland and I think you’ll get close to what he was thinking of. In this particular illustration the rabbit wears a coat decorated with hearts and is blowing a trumpet to announce that he’s about to read out something important that he’s holding in his other paw. That all fits Peter Klann. He had a message and he lived that message. Bread was his medium in every sense of that word.

If this still seems a bit cryptic let me ask a rhetorical question. What would a world where there is no balance between love and food look like? Well, we don’t need to look far to find out! Our world is certainly one where food is available in much greater quantity than love. Here I think it’s worth pointing out that since the late 1930s “bread” has also been used to refer to money. It seems that this goes back to the jazz hipsters of New York City, legend ascribing it to the saxophonist Lester Young. Whether that’s true or not, “bread” shares the same origin as “hip” and “cool”, although back in the New York of the 1930s those words meant something very different to what they do today, something strong and individualistic, rather than referring to those who follow all the fashions with a herd-like mentality. Peter was acutely aware how the great availability of bread, in both the literal and metaphoric sense, and the widespread tendency to accept it in place of love had promoted that herd-like mentality, and it pained him.

Now I’m sure that it is possible to describe in a scientific manner how Peter made his bread and explain what made it taste so special (thanks Ben for proving that to me by providing part of that explanation!) However, I think if someone does that and leaves Peter out of the equation, then they will make the mistake of creating a different kind of unbalance between love and food. Peter was at once a strong and extremely gentle man, a thinker and a doer; he was restless yet utterly dedicated to his goal. Without all this, as contradictory as it often seemed, I think a huge chunk of the context of Peter’s bread would be lacking, and as Friedrich Nietzsche wrote, “the context is the facts.” Call me superstitious, irrational, or whatever else you want, but I believe that if you open the doors of perception and eat a piece of bread from Soluna (or from Ben and some other ex-Soluna employees), then you can taste something of Peter’s message. Sure a winemaker or a baker must master their trade, then work with dedication to realize their goal, but I think that often you can taste where all of this was done with love. And that has nothing to do with “bread” in the other sense.

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12001.jpg)

I’m not that much of a online reader to be honest

but your sites really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your website to come back

down the road. All the best