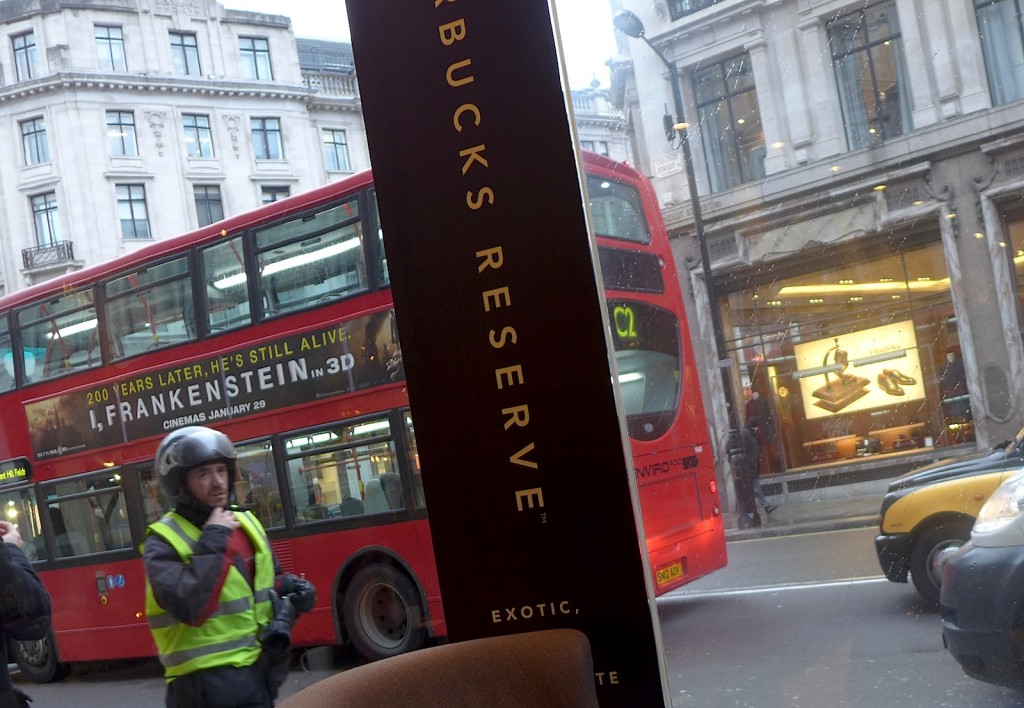

Outrageous! The energy and creativity, greed and arrogance of London are right outside the window as I write this (above) and I don’t think there’s anything I need to say more about them than to observe that I’m currently torn this way and that by them. Instead let’s turning the clock back a few days to my visit to Winzerhof Stahl in Auernhofen/Franken and my tasting of Christian Stahl’s (below) embryonic 2013 wines.

Outrageous! The energy and creativity, greed and arrogance of London are right outside the window as I write this (above) and I don’t think there’s anything I need to say more about them than to observe that I’m currently torn this way and that by them. Instead let’s turning the clock back a few days to my visit to Winzerhof Stahl in Auernhofen/Franken and my tasting of Christian Stahl’s (below) embryonic 2013 wines.

With just 150 inhabitants the sleepy hamlet of Auernhofen is about as far removed from Central London as you could possibly imagine. “Where the hell is that???” asks London looking down its long nose. The thing that London could never believe about Auernhofen is that, as well as growing a lot of wheat and using most of it to raise pigs it is also home to the Quentin Tarantino of Dry White Wines (as I christened him back in 2009). Already when I first met him a decade ago Christian Stahl was turning what “ignoble” white grapes like Müller-Thurgau and Bacchus can do upside down. Since then he has expanded this endeavor to include Silvaner, Scheurebe and the supposedly “noble” Riesling and Sauvignon Blanc grapes (which he reinterprets no less radically). However, Christian isn’t just a talented winemaker he’s also a thinker who pulls the myths of the wine world apart as if they were so much pink candy floss!

For him the terroir theory of wine is pushed way too far by some of its proponents and he pours scorn on the idea (let’s face it this is part of many sales pitches) that, somehow, those wines widely praised as being the ultimate expression of terroir are produced without any winemaking taking place; as if terroir removed the need for winemaking and enabled the production process to happen all by itself. The truth is that all wines are made, at least in the sense that they’re all the result of various decisions being taken in the press house and cellar, certain techniques having been chosen in preference to other possible methods.

The best argument in favor of this position are Christian’s 2013s wines, which strike me as being a remarkable work-in-progress. They have a racy brilliance and cool fruit aromas and mineral freshness that make me long for hot days and balmy evenings. For Stahl the harmonization of this vintage’s substantial acidity is the greatest challenge in the cellar (assuming that only clean grapes were used, which doesn’t go without saying in this rot-prone vintage), and the normal German method of using a few grams of unfermented sweetness to do this job is really a last resort for him. Lees (the deposit of yeast left after fermentation) contact, lees stirring and some cautious use of malolactic fermentation (which turns the “unripe” malice acid in wine into the softer lactic acid) are his main methods of achieving this. However, if a small amount of chemical deacidification helps, then he doesn’t hesitate to do that. The proof this works is the wines success in the German market.

Christian is also an excellent cook (see left) and I’d certainly have given the guinea fowl breast he cooked after our tasting a Michelin star if I’d been a tester. No wonder his wines sell so well in the good and great restaurants of Germany (right up to Tantris in Munich!). I think his excitement about cooking and food has driven the development of his wine style, and it wouldn’t surprise me if he started an even more ambitious gastronomic venture than the excellent catering he and his wife Simone already do at their estate. Then the story of this winegrower who’s name means steel and who has steel in his soul will enter a new phase that London will find even more impossible to understand. However, the truth is that he doesn’t need the London market, just like a bunch of other German Jungwinzer!

Christian is also an excellent cook (see left) and I’d certainly have given the guinea fowl breast he cooked after our tasting a Michelin star if I’d been a tester. No wonder his wines sell so well in the good and great restaurants of Germany (right up to Tantris in Munich!). I think his excitement about cooking and food has driven the development of his wine style, and it wouldn’t surprise me if he started an even more ambitious gastronomic venture than the excellent catering he and his wife Simone already do at their estate. Then the story of this winegrower who’s name means steel and who has steel in his soul will enter a new phase that London will find even more impossible to understand. However, the truth is that he doesn’t need the London market, just like a bunch of other German Jungwinzer!

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12007.jpg)