Once again I’ve managed to get myself in trouble by looking for the truth in wine, although this time it’s an aspect of wine that has nothing to do with the taste: wine prices and the profits they make both for the producers, and for those who trade in their products. The question that drives me in this research is where does wine stop being a beverage (however “sophisticated”) for which the winegrower works hard and from which she or he makes a more or less good living, and when does it become part of the world of luxury goods along with designer handbags and sports cars. What interests me is not prejudice or politics, but the hard economic truth in wine.

Once again I’ve managed to get myself in trouble by looking for the truth in wine, although this time it’s an aspect of wine that has nothing to do with the taste: wine prices and the profits they make both for the producers, and for those who trade in their products. The question that drives me in this research is where does wine stop being a beverage (however “sophisticated”) for which the winegrower works hard and from which she or he makes a more or less good living, and when does it become part of the world of luxury goods along with designer handbags and sports cars. What interests me is not prejudice or politics, but the hard economic truth in wine.

The trouble began when I started publicizing the first results of my investigation into what would be the highest possible average production costs for a dry white or red wine produced regularly from the same piece of land (where many factors are fixed) which has been inherited by the producer. I kept hearing a figure of about €6 / $8 per bottle as the maximum for high-end wines grown on steep slopes where cultivation is almost largely manual and crop levels are 30 hectoliters per hectare / two tons per acre or slightly less. Perhaps, by pushing the density of vine planted to the extreme (which may not necessarily be good for quality) and by cutting yields down even further (to levels which are very rare) one might come up with growing costs of as much as €12 / $15.50 per bottle. Let us then allow for two years of aging in 100% brand new barrels (don’t forget that after use they’ll be sold on, not thrown away) and fancy packaging. This takes us to a about €20 or $26 per bottle for something like Grand Cru Burgundy. Only by piling on the marketing, financing and other indirect costs can it go much higher than that.

I happen to know from an earlier research project that for the top red Bordeauxs production costs are significantly lower than the theoretical maximum figures I’ve just calculated. In March 2007 I visited Bordeaux as the guest of Millesima, a negociant who sells directly to the consumer, to take part in their overview tasting of the 2005 vintage. The wines had either just been bottled or were just about to be bottled. To me it tasted like another excellent vintage, comparable in quality to 1982 or 2000, but a tad more elegant than either of them. Immediately afterwards I was received at Château Haut-Brion where I tasted the 2005 red wines, which were just about to be bottled, and was very impressed. Best of all was the 2005 Haut-Brion itself, which then tasted much the way the Château’s website describes it, “creamy, big, powerful and fresh”. But today, we’re looking for the economic truth in wine, not for origin of the pleasant taste.

At the airport I looked at the price list for the 2005s which I’d been given at Millesima and discovered that the 2005 Château Haut-Brion would cost me more then €650 / $845 a bottle. Ouch! Then, I got in touch with my Bordeaux spy who had the most amazing contacts in the region. She knew roughly what the production costs for Haut-Brion were and when I told her to add a healthy amount for marketing, financing, etc. she still came up with a figure of under €20 / $26 per bottle. I insisted that we round it up to this figure to show good will. Then she told me that the lowest price at which Haut-Btion had sold this wine into the market was €240 / $312 per bottle. This leaves a minimum profit of €220 / $286 per bottle, which is a profit margin of at least 1,100%. The production quantity of 109,000 bottles is well known, so it s possible to calculate a minimum profit for this vintage of this wine. It would appear to be well in excess of €24 million / $31 million. Perhaps there are enormous costs which I’m not aware of, but I find this hard to believe. Of course, Millesima and many other traders also made hundreds of Euros profit per bottle on this wine, and on others which are in the same league.

This is, of course, market forces and the way of the world. For me the question is not if it’s immoral, much less whether it should be allowed to happen. However, I think it’s better for us all if we don’t pretend that the profits made on this kind of wine – call them high-end wines, collectible wines, investment wines or whatever – by the producers are in the tens of percentage points range as they are in so many other businesses, also in the t other business which is the wines to drink made and consumed in the real world. Let’s see this phenomenon for what it is, which is part of the luxury goods industry and bling.

I have to admit that going through these figures didn’t stimulate my thirst for Grand Cru Burgundy or Premier Grand Cru Classé Bordeaux. Instead I’d rather have a nice glass of Riesling with which the producer has earned himself a good living and enough money to invest in the further development of his company. That is my Planet Wine.

PS A couple of years later in Zürich I encountered the 2005 Château Haut-Brion again in a blind tasting. I had no idea it would be there, so I think you could call this “double blind”. The wine had a lot of dry tannin and was quite powerful, but very lean. The most obvious aroma was of green bell pepper, a character typical of unripe or (more likely in this case) half-ripe Cabernet Sauvignon grapes. I wasn’t the only taster to be seriously disappointed by this wine, but the sad thing in this case is that the taste doesn’t really matter.

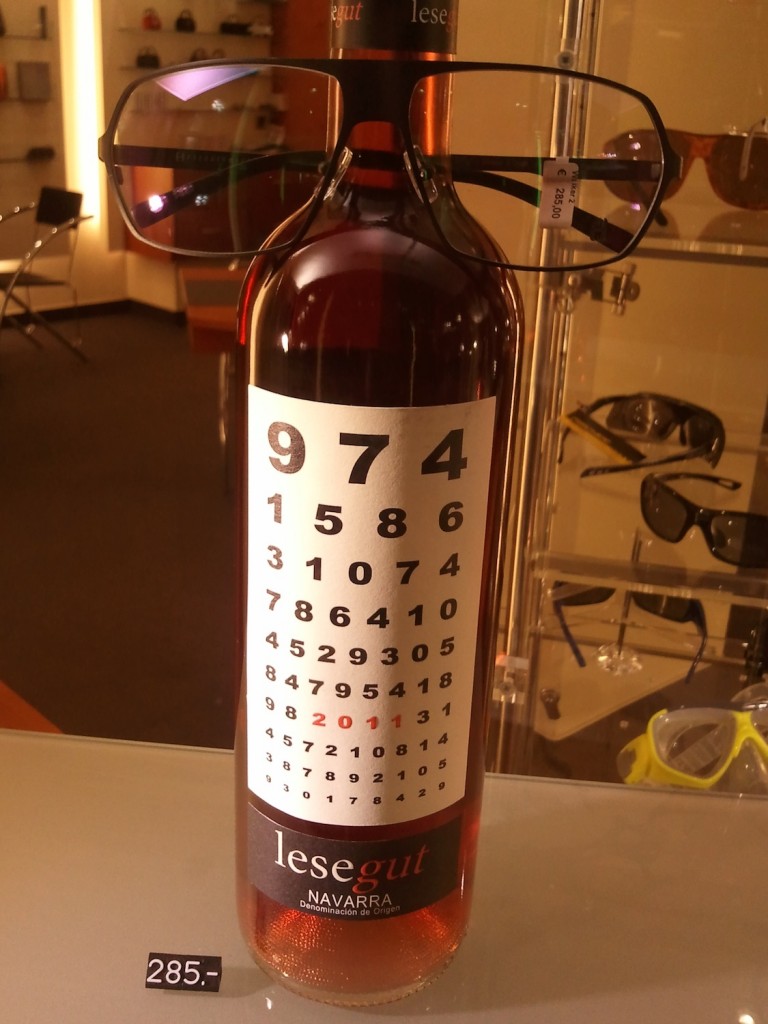

Thanks to Birgitta Böckeler for the photograph!

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x120014.jpg)

Many thanks for this entry. That’s what I always suspected, when looking at the prices of some french and american wines. But even german wine prices reach high levels. What do you think of the prices sold on auctions for wines from Müller-Scharzhof or Fritz Haag. Are they also overdrawn?