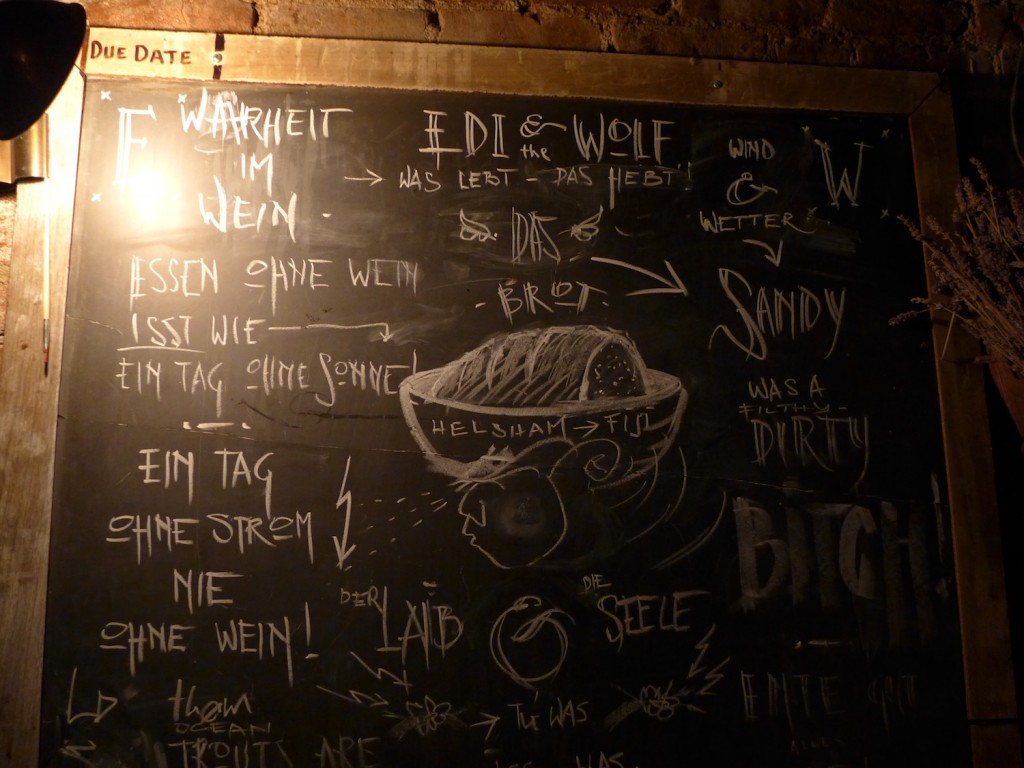

As the blackboard at Edi and the Wolf on Avenue C at East 7th Street where I had dinner last night boldly declares there is Wahrheit im Wein, truth in wine. I like this ancient saying precisely because it’s highly ambiguous and allows all manner of interpretations. The stereotypes I was talking about yesterday often obscure the truth in wine, but like all the other 57 varieties of stereotypes those for wine are sometimes true. For example, I am an eccentric Englishman, and if you’re in a crowded NYC restaurant mid-evening, then you’ll probably be surrounded by New Yorkers shouting at each other over the table.

As I explained yesterday Riesling is by no means always the sweet German wine so commonly supposed. However, sometimes it is exactly that and is also a intense and inspiring taste experience. This particularly applies to the wines of the northerly regions of Germany, that is the Mosel, Saar, Ruwer, Nahe, Mittelrhein and some parts of the Rheingau. One of the handful of special bottles I schlepped over to New York from Berlin is a 1990 Riesling Auslese from Zilliken in Saarburg on the Saar that is a perfect example of this special type of Riesling. The combination of a rather cool climate with great daytime-nighttime temperature fluctuations and stony soils in these German river valleys (another Riesling stereotype that’s true in this case) makes these dangerously refreshing and seductively aromatic Rieslings possible. Many wine lovers consider them unique, but this is not quite true, for top producers in New Zealand like Felton Road and Framingham have also mastered the production of this type of Riesling.

Wherever it comes from this type of Riesling is fruit-driven and needs the pronounced acidity typical of those wines. This balances the natural sweetness left in the wines when the fermentation is stopped before much of the grape sugar has been turned into alcohol by the yeast (for which reason the wines are also low in alcoholic content). And there we have yet more Riesling stereotypes which happen to be true in this case, namely that Riesling is a light and tart wine.

Why has this special type of German Riesling struck such a nerve in the English-speaking world? I think it has to do with the (almost) uniqueness of the flavor profile, but also with the fact that for a long time the good and great producers of those northerly regions of Germany concentrated on just this one style of wine from one grape variety. The French way of thinking wine about wine which is baed on the idea that each winegrowing region is destined to produce just one type of wine (or at most one type of red and one type of white) long ago became the way the English-speaking world mostly thinks about wine. For a long time the Mosel came very close to fitting this francophile preconception of how wine should be, though the Germanic wine tradition (not only in Germany, but also Austria, German speaking Switzerland, Alto Adige in Italy and Alsace despite it being in France) is one of diversity of grape variety and/or wine type within each region.

Yesterday evening I ate a delicious beef filet with spinach and mushrooms and drank some good Austrian red wine at Edi and the Wolf, but after I finished eating I really missed a glass of the rather full-bodied, but vibrant dry Rieslings that Austria produces. It would have been so right for the very New York atmosphere of this place where cultures intertwine in accordance with the stereotype of this city as a melting pot.

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12004.jpg)