This photograph shows “sunburned” Riesling grapes in the Mosel Valley immediately after the second extreme heat wave of 2019 Germany in late July. No less than the melting ice cap of Greenland or the catastrophic damage just caused in the Bahamas by hurricane Dorian it should be regarded as a warning of what it is to come. Things are moving fast and we need to act now before it is too late.

Almost six weeks have passed since I gave my seminar about Riesling in regions with warm and warming climates titles Wrong Side of the Tracks at the FLXcursion conference in the Finger Lakes (FLX), Upstate New York/USA. It’s now high time for an update on the latest developments regarding climate change and it’s influence upon wines made from the Riesling and other grapes in what used to be the cool climate regions of Europe and of the other wine continents.

My last blog posting (scroll down) ran under the headline Cool Climate is Dead in Old Europe, because during my research for my FLXcursion seminar I came to that conclusion. To be precise, if it is a decade or more since there was a genuinely cool vintage in a winegrowing region, then I don’t see how that region can be called “cool climate” any longer. For the Riesling regions of Germany 2010 was the last cool year (and the one before that was 1996). Of course, as I wrote, how the wines taste is another matter and I’ll return to this point after we’ve looked at the weather stats of the last three months for Norheim in the Nahe Valley. I have a particular interest in the Nahe, because I work as Riesling Ambassador at the Gut Hermannsberg (GHB) estate just upstream from Norheim, with the nearest weather station. I therefore experience much of this personally too.

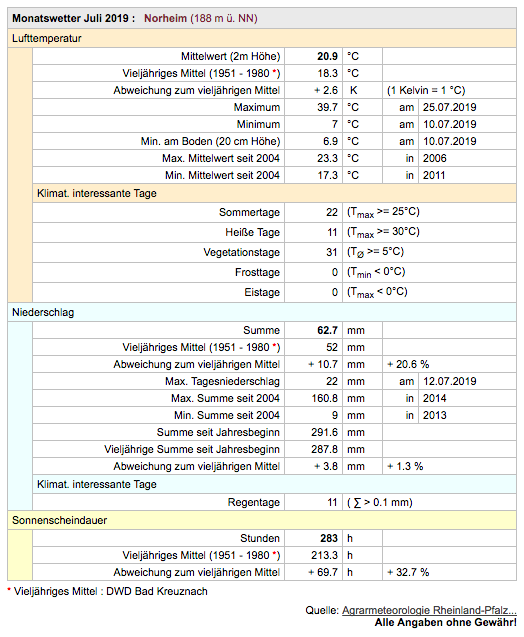

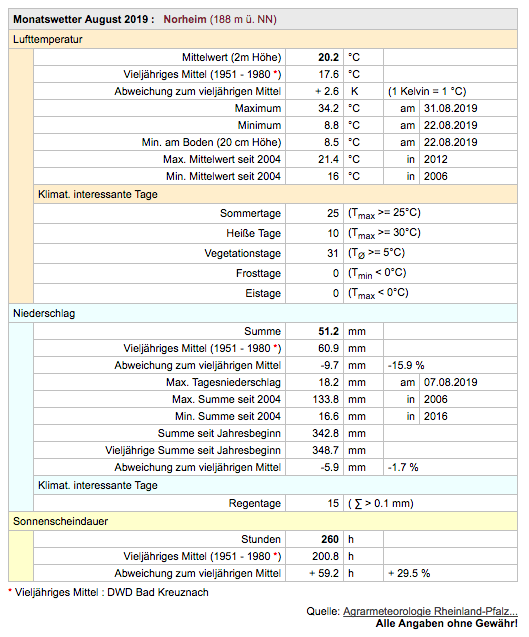

The weather summary for June 2019 in Norheim is below in my previous blog posting, above is that for July 2019 and below for August 2019. In all these months the monthly average temperature was just above 20°C, which means that in both July and August it was 2.6°C above the late 20th century (1961-1990) average, and in June it was 3.9°C above that figure. This results largely from the high number of warm days with the temperature reaching or exceeding 25°C on 67 days and 30°C on 31 days – more than a third of all 92 days! – during this three month period. On only 25 days – less than a third of all days – did it fail to reach 25°C. There was one heat wave each month, the maximums recorded for each being 39.6°C in June (on the 30th), 39.7° in July (on the 25th) and 34.2°C in August (on the 31st).

This lines up with the total of 840 sunshine hours during the last three months, with 297 hours in June alone. That’s 42.4% above the late 20th century average! This is something with fundamental implications that’s far too little discussed in the German wine scene Rainfall is the other side of this equation. After the extremely dry June with just 18mm of rainfall we were lucky there was slightly more than 50mm of rain in both July and August and this was enough to keep the vines in decent shape. And if that’s the case on the extremely stony soils at GHB, then it should be no great problem elsewhere in Germany.

Except where there was massive sunburn damage late July the vineyards of Germany look very good as the Riesling grapes go into their last ripening phase. Picking of the pinot family of grapes (another quarter of Germany’s whole vineyard area) will begin much sooner and they also look good. Thankfully the acidity levels look healthy. However, that doesn’t mean 2019 was a “normal” year. I now expect that the growing season average temperature will not be far below the figure for 2018, the warmest growing season ever recorded in Germany with an average temperature of 18°C. Compare that figure with the late 20th century average of just 14.5°C and 16.9°C, the average for the warmest year of the 20th century, 1947, to get a feeling for what has changed and how fast.

The truth is that nobody knows how the 2019 wines will taste. It may be counterintuitive, but in 2018 GHB, along with many other German Riesling producers with vineyards on stony soils, made wines that still have cool climate characteristics. By that I mean they have bright aromas, sleek body, and a refreshing acidity. Analytically this translates into moderate alcoholic content and low pH. The problem is that what happened in 2018 doesn’t mean that in 2019 German Riesling producers are in the clear, only that they have a good chance of not losing the “cool climate” characteristics that historically made those wines special. I wish them the best of luck.

The next instalment of this story will look at developments in a distant location in North America where things are also changing fast. This is a local and global challenge and we need action on both those levels!